Text from 'Moving Images', web-exhibition series, Centre for Contemporary Photography, 17 July – 21 August 2020.

Arini Byng is a Naarm (Melbourne)-based artist whose ‘body-based’ work is concerned largely with the affective qualities of materials, gestures, and settings to enter into socio-political conversations. Her 2018 work (indistinct chatter), a 12 minute and 58 second single-channel video, has previously been impressively exhibited in large-scale wooden scaffolding as part of group show A sinking feeling (the politics of risk) at Blak Dot Gallery in 2018. CCP is excited to show (indistinct chatter) online in full for the first time as a part of the web-exhibition series Moving Images. Below you can read dual responses to the work, switching between Arini Byng’s writing providing biography and context, and CCP’s image-reading perspective.

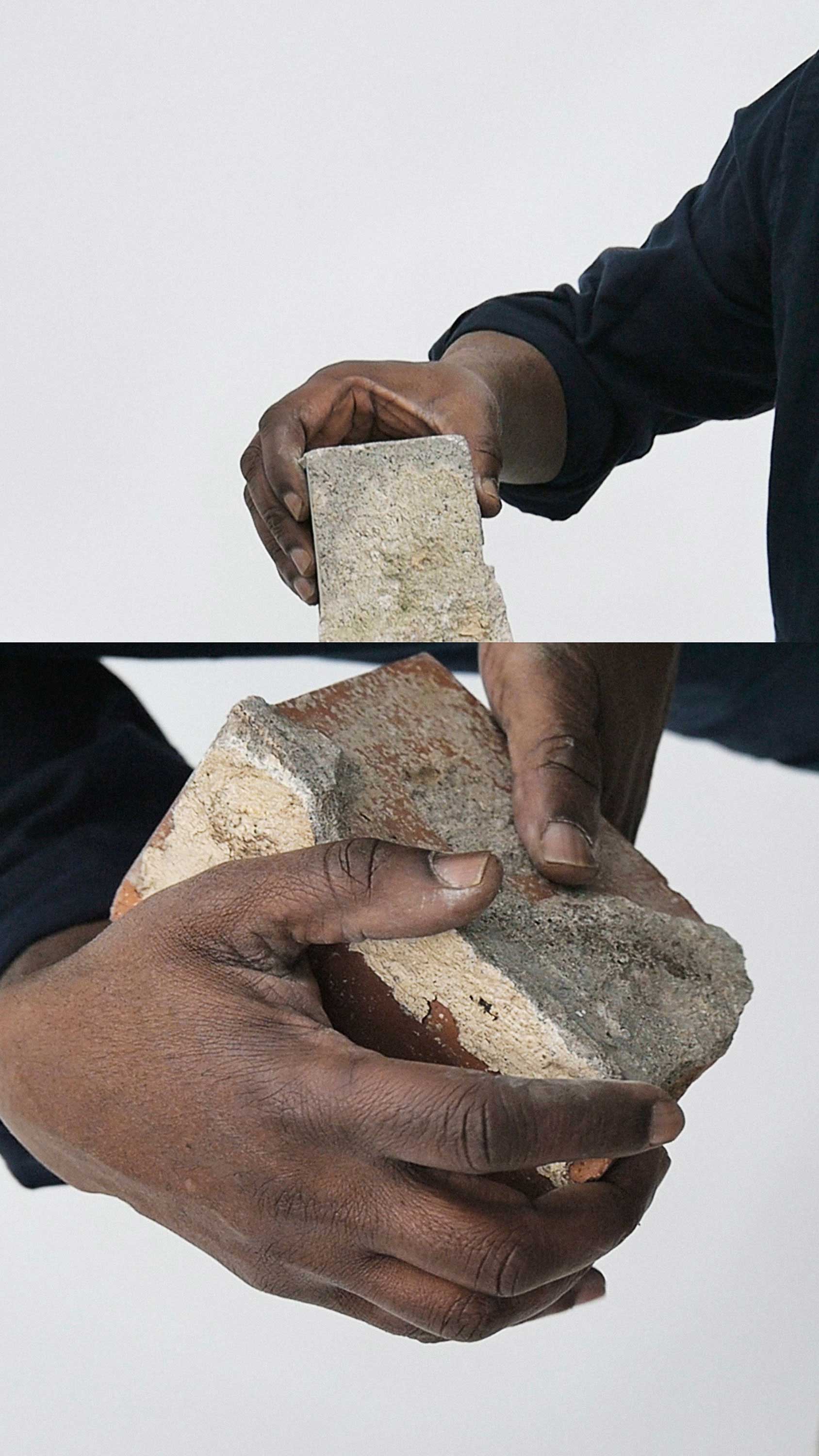

Arini Byng: (indistinct chatter) is an intimate and personal work with only my father and myself on screen, in an improvised duet. We negotiate with each other's limbs, vulnerably and tenderly but also with the subtle tensions inherent in the discovery and exploration of cultural and familial themes. In the dance, that the piano periodically reminds us is taking place, the introduced objects serve as material juxtapositions to the soft limbs. Though more importantly, they serve as personal and historical markers for the dancers who must build their new forms around them.

Byng’s description of (indistinct chatter) as an ‘improvised duet’ is unlikely to take viewers by surprise. Subtle cues — the intermittent piano score chiming as if tuning or warming up; the slight sense of caution in Byng and her father’s hands — point to how the artists are discovering their movements alongside the audience. While improvisation is a central mechanism of the work, so too is the idea of the ‘duet’.

(indistinct chatter) is a duet in many senses. To the eye, in its physicality and dance shared by two figures. Through improvisation, it is a duet in authorship. While Byng has dictated the setting and aesthetics of the work, her father is an equal partner in the creation of movement. Moreover, the work is a duet in dialogue. Much in the way that single notes and fragments of melodies hint at a larger possible song, the full content of this exchange between Byng and her father is not clear to us. Audiences may find moments of comprehension, filtered through their own understanding of parent-child dynamics, but details of Byng’s own biography and relationship with her father remain private.

The emotional range of familial relationships and histories now common in our culture all played a part in my decision on what objects to include. I thought that they should speak of our nuclear family's particular two-household history, to the history of our family in Black America, and to perceptions of that history.

In a work that is aesthetically minimal, the objects chosen to fill the visual field are laden with meaning. The industrial materials handled over the 13 minute run-time of (indistinct chatter) are evocative of Byng’s family roots in manual labour as a means of income. Through the handling of cemented bricks and industrial wooden planks, this intergenerational meeting lets the audience in on an intimate but, as Byng indicates above, shared cultural experience. The rhetoric and mythos surrounding the notion of class ascent through hard work is common in Australia and the United States, as well as many countries with similar economies, cultural ideals and histories of labour. This can result in an inherent tension between parent and child, as they seek to reconcile their intergenerational class differences (and commonalities), which we can see played out in the co-authored choreography between Byng and her father. The intersections of class and race, already inseparable, are made even more accessible in the work with the added understanding of a little of the artist's biography.

My father grew up black working-class in the American northeast in the '50s and '60s. It was a time when American manufacturing and production were still centred in that region and anyone who wanted to work could find employment. Because of the colour of their skin however, for years his parents worked three jobs between the two of them before they could become home-owning members of the [Black] American Middle Class.

From Byng’s writing, it becomes clear that their duet mirrors one undergone by Byng’s father and his own parents, placing Byng and her father’s dialogue in a network of exchanges.

In carrying out this dialogue, the artist’s own arms and those of her father share the screen. Their bodies are cut off by the frame, though thrillingly, there are very occasional glimpses of a head or face. This abstraction provides an entry point for the viewer. We understand that Byng and her father are present and therefore speak from a complete and embodied position, yet (indistinct chatter)’s focus upon arms and hands as sites of action highlights the negotiations, holdings, and eventual embrace of the figures. In this way, Byng provides a visual vocabulary for the kind of negotiation and knowledge-exchange common to many, but in particular to those from Black working-class backgrounds such as the artist.

The introduced objects address not only this Black American history but also the personal histories of children from divorced households anywhere - exploring the possibilities, problems and potentialities of reconstructing relationships with an absentee parent. Constructing these explorations in the context of a dance returns the participants to their original state of pure co-dependence while also addressing cultural resonances.

The final few minutes of the video offer up the relief of Byng and her father’s hands finally meeting. After extended grappling with bricks and wooden planks, their arms meet to apply lotion. The two figures come together and tend to each other — an act of ‘doing’ that feels so constructive after watching the hands negotiate and understand the industrial materials. As Byng indicates in the first paragraph of this text, the objects “serve as material juxtapositions to the soft limbs”. Mirroring ideas of ‘public’ and ‘private’ life, all the more relevant as people’s work increasingly infiltrates their homes under lockdown, the tenderness and care of the application of lotion feels akin to the release of the end of the work week. While not necessarily judgemental or critical in her treatment of the symbols of physical labour, Byng’s eventual depiction of shared care-giving speaks to a reconciliation between generations, an answer to the otherwise potential alienation being negotiated throughout the work.

The title relates to a caption seen in films when there are multiple audible conversations taking place, but no particular dialogue is discernible...(indistinct chatter) is the noise of people who are taking no notice of a soundless, wordless exchange of information taking place in the foreground of the scene, to the left of centre stage.

In this work, Byng takes this background noise and brings it to the foreground. She acknowledges a conversation that is not often deeply examined, without reducing this exchange to a retelling for voyeuristic eyes. Through the abstraction of this improvised duet, we’re invited both to consider the specificity of Byng’s family narrative, and to investigate how we handle and share our own memories, experiences and relationships.

See the article in full here.